conference

in oktober 2016 Alnarp University hosted the conference 'beyond ism'. The aim of this conference was to reposition the relationships between city and landscape, as reflected in the practice and academia of various disciplines. To this end, the academic discourse concerning Landscape Urbanism was revisited, to engage with subsequent ‘isms’ as well as looking beyond, in order to enrich and broaden the urban discourse. I presented two papers at the conference.

sensory landscape experience

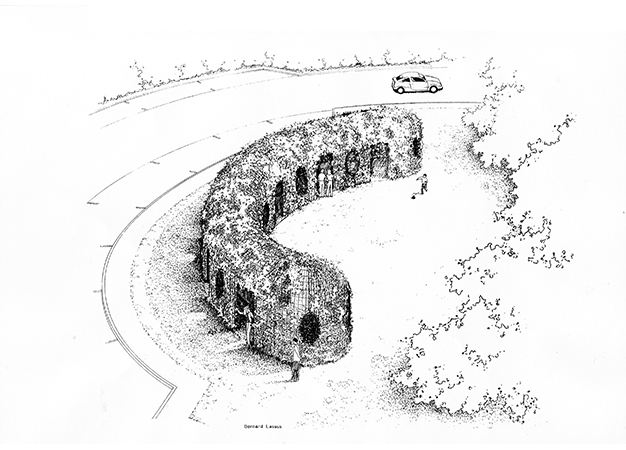

Gardens and motorways represent inherently different ways of perceiving the landscape: while the motorway is a purely visual experience, seen through the windshield, distanced from the perceiver in his climatized cocoon, the small, tactile scale of a garden allows for a multisensory experience. With motorways getting more and more separated from their landscapes, can a garden be the opportune resource to address the motorway landscape? A place that appears to be doing this, is the Garden of Birds, a small circular space as the pivot point of a rest area along the A837 motorway in south-western France. Fifteen years after implementation it now appears more like a garden than might have ever been intended, providing a sensory landscape experience. Drawing and describing this situation—including its intentional and unintentional changes resulting from manmade and natural interventions and processes—as if it were a designed composition, exposes a spatial elaboration that facilitates the multisensory perception of landscape. The garden experience entices the motorist to look at the surrounding landscape with fresh eyes.

This paper was published in JoLA 3, 2016.

the garden and the layered landscape

The contemporary notion of landscape urbanism seems to be obsessed with horizontality and large scale-organisational techniques, in favour of object and spatial form. But is that such a good idea? Aren’t we thus letting go of the specific spatial and experiential qualities of the landscape and of the architectonic culture in which these landscape qualities can manifest and develop? The garden has always been a place where urbanism, architecture and landscape are seamlessly intertwined. It is also a small scale, defined object with a formal, spatial design, which does not appear to deserve a place in the definition of landscape urbanism. If we were to give it a place, what could that be, and what can landscape urbanism learn from the design of gardens?

Rather than viewing landscape urbanism as a new member in the growing and hybridizing family of design disciplines, in this respect it might be helpful to realize that in its essence urbanism already is nothing more than a new layer of the already layered landscape; urbanism based on landscape principles is from all times. The physical-spatial development of the landscape crystallizes in stages. The natural, cultural, urban and architectural landscape (whether latent or present) each has an organization and form of its own, which is never the result of only the last transformation, but showing traces of the layers underneath. Even in the traditional, centralized city, surrounded by open landscape, landscape and city are interacting entities. The contemporary metropolitan landscape can be considered an overall hybrid of all shades of urbanization, which is not so much a new concept, but a change of emphasis, in which the boundaries have blurred and thickened until they began to take more space than the original counterparts.

Gardens are a reflection of these different layers of landscape, regardless the urbanity or non-urbanity of their context, and as such have the ability to make connections and catalyse new developments. A striking example is the quadrangle of St. Catherine’s College (1960) in Oxford by Arne Jacobsen, transferring a traditional Oxford courtyard type to the open landscape of the river meadows. As a modern design it seems to stand for everything that landscape urbanism does not: trying to contain the dynamic multiplicity of urban processes within a fixed spatial frame. But the garden connects the different functions—changing over time—within the college, as well as in the city and the fields. It also reflects the different layers—natural, cultural and urban—that characterize the development of the Oxford urban landscape. Within an urban-landscape dichotomy there would have been only two choices: incorporating the location into the urban fabric or not building and preserving it as open landscape. Instead, the design gives room to local qualities, and highlights the possibilities of the open landscape as integral part of the urban landscape. The galaxy of gardens that defines Oxford serves as model for urbanism, not determining the city, but as an open-ended pattern stripping away the duality of inside and outside, of city and countryside. It does not belong exclusively to the urban realm, but it uses the tools and images of the landscape to relate to a range of specific conditions.